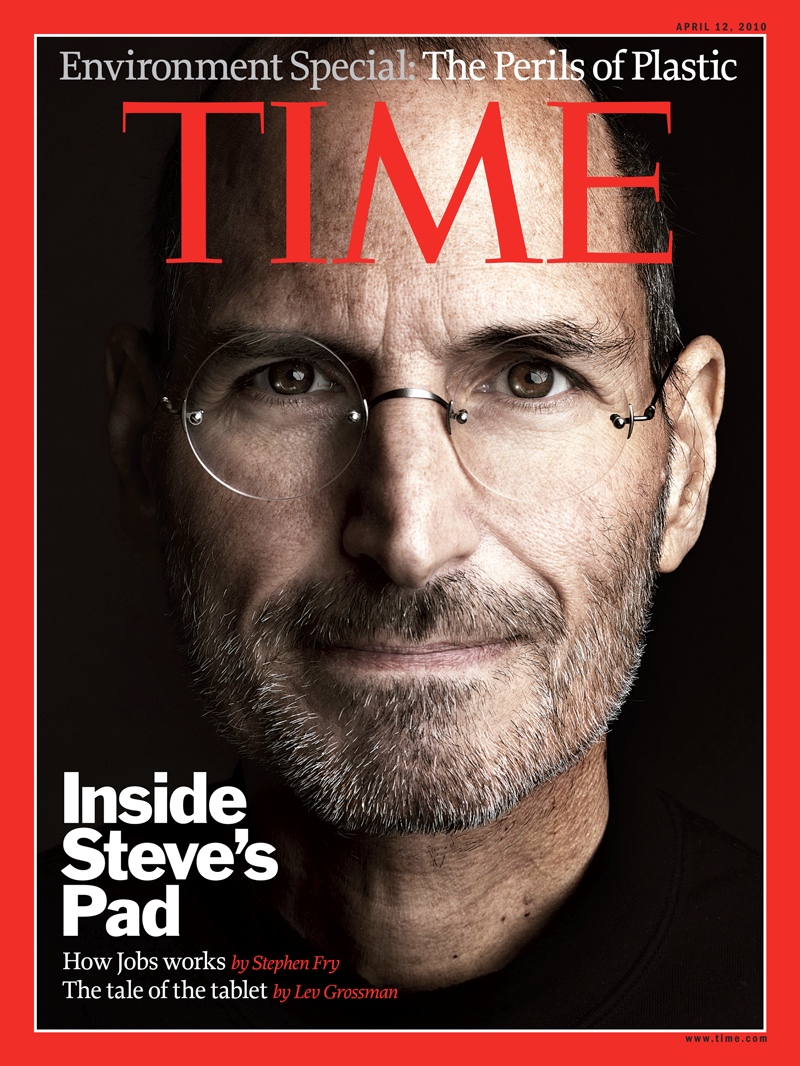

Why Did Apple Give In On Controversial In-App Subscription Policy, Anyway?

June 11, 2011

By now, we all know Apple has famously revised its infamous in-app subscription model. As our Joe White already explained, the old policy, discussed in section 11.13 of the iOS Developer Agreement, runs as follows:

Apps can read or play approved content (magazines, newspapers, books, audio, music, video) that is sold outside of the app, for which Apple will not receive any portion of the revenues, provided that the same content is also offered in the app using IAP at the same price or less than it is offered outside the app. This applies to both purchased content and subscriptions.The new policy, however, removes the clause that called for identical content to be made available via in-app purchases "for the same price or less" than any externally-sourced data. Instead, such apps are simply disallowed to link to that paid information. Section 11.14 reads thus:

Apps can read or play approved content (specifically magazines, newspapers, books, audio, music, and video) that is subscribed to or purchased outside of the app, as long as there is no button or external link in the app to purchase the approved content. Apple will not receive any portion of the revenues for approved content that is subscribed to or purchased outside of the app.Frankly, I didn't see the move coming, though I doubt Cupertino was strong-armed by the likes of Financial Times and the newspaper's HTML 5 app alternative. More likely, says MG Siegler over at TechCrunch, Apple simply

had an idea, one that would potentially be hugely profitable for them, and they decided to test the waters on it. They put it out there to see if it would swim. It sank. So they reeled it back in and changed things. All of this happened, mind you, before anything was ever actually changed. I’m sure it’s a total coincidence that Apple just altered these guidelines right before the changes were due to take effect later this month.While I agree with Siegler's thoughts on the matter, I doubt it was mere "coincidence" that saw Apple change its approach so close to the implementation's deadline. Rather, I expect it was a combination of factors -- including public perception and the tedium of constantly working with content publishers on "special terms" -- that led to Apple's reconsideration and eventual redirection. Logically, now was the best time to make such a change, and it's probable that Apple set the June 30 cut-off as much for their app-makers as for themselves. Additionally, I think Apple had enough of a chance to gauge where their old subscription model would lead both the makers and the takers, and they didn't necessarily like what they saw. As I mentioned in my take on the Financial Times web app effort, the end-result of that route just isn't capable of pulling off the slick graphical tricks and matching the speedy performance of dedicated, Objective-C iOS applications. If enough publishers bailed out of iTunes to make inferior products run on iPhone and iPad, it could have a perilous cheapening effect on the perceived worth of Apple's hardware and software experience. No matter the level of competition, that's never a good thing. Still, I think Apple should go ahead and (eventually) allow publishers to charge whatever they want for subscription or paid content within the apps themselves. If a $10 book on Amazon's Kindle service costs $13 in iTunes, I think Apple might be surprised at the amount of people willing to pay that premium for seamless integration on their device of choice. Of course, as Amazon is probably going to be Apple's only heavy (and heavily-capable) competition in the tablet hardware arena, this particular scenario might be a bad example. Overall, though, I'd bet most of us like to buy subscriptions within our apps if at all possible; and -- if Apple allows publishers to set their own prices even for only a short trial period, they might learn quite a lot more about their user-base's spending habits. To be clear, I was quite in favor of Apple's demands (including their 30 percent take off the top), as I feel the company has every right to push the limits of what kind of money its own market can generate. However, I do believe that, for the various affected publishers, this solution is far better and likelier to lead to increased attention on Apple's mobile lineup. And, though it may cost the end-user some small semblance of iOS' highly-touted user-friendliness (necessitating external subscriptions is inconvenient, after all), those individuals will be able to reap the rewards of said greater attention and support. Apps, publishing, and subscriptions aside, Siegler says there's an important message to be learned from all this: "Apple is not stupid." The company always adapts, altering its market approach as public and private reactions warrant. And this won't be the last time they have to do that, either. Oh, and welcome back, BeamItDown Software! I guess Apple didn't screw you after all.